Following emotional trauma, people may develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as flashbacks, avoidance of reminders of the event, negative cognitions or mood, and hypervigilance (1). Observing that some clients with these symptoms seek an understanding of why they experience them, David Leong, MA, LMFT, created and often starts off therapy with a “story” about the neurological effects of trauma on the brain (2). While David notes that his story (based on work by Dr. Dan Siegel) might be over-simplified, he finds his clients find it helpful. This post is a summary of the story:

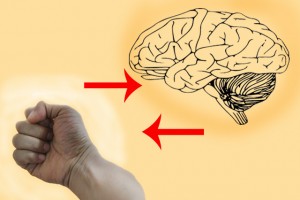

The brain can be thought of as a fist: Your forearm leading up to it is the spinal cord, and the base of your palm is your “lizard” primitive brain, that manages such automatic body functions as heartbeat and sweating. Next, if you fold your thumb sideways across your palm, this is your mid-brain—your “limbic system.” It houses emotion, memory formation, and the “fight or flight” response. Two important structures within it are the amygdala, thought to be a key player in emotional/fear/implicit memories (3,4), and the hippocampus, thought to be a key player in converting information into memory codes (4). The “language” of the limbic system is emotions. Finally, if you fold your fingers over your thumb, you have your cerebral cortex, which speaks in words, and houses sense of time and explicit memory—a more abstract, gist-based, structural recording of episodes than implicit memory (3).

The brain can be thought of as a fist: Your forearm leading up to it is the spinal cord, and the base of your palm is your “lizard” primitive brain, that manages such automatic body functions as heartbeat and sweating. Next, if you fold your thumb sideways across your palm, this is your mid-brain—your “limbic system.” It houses emotion, memory formation, and the “fight or flight” response. Two important structures within it are the amygdala, thought to be a key player in emotional/fear/implicit memories (3,4), and the hippocampus, thought to be a key player in converting information into memory codes (4). The “language” of the limbic system is emotions. Finally, if you fold your fingers over your thumb, you have your cerebral cortex, which speaks in words, and houses sense of time and explicit memory—a more abstract, gist-based, structural recording of episodes than implicit memory (3).

Now, the brain processes events “bottom up.” So, if it encounters a threat, such as a barking dog, it feels and reacts first (with the lower, limbic system), and thinks later (with the higher, cerebral cortex). In the case of the barking dog, the limbic system would cause you to jump first, before your cortex can enter the process, and then the cortex may recognize that the dog is attached to a chain, and you’ll calm down. Once this happens—this collaboration—then under normal circumstances, someone is not typically left “traumatized.” (2)

However, sometimes, the stimulus is so powerful that it overwhelms the amygdala and hippocampus, and “short-circuits” this collaboration, such that the fear and panic don’t reach the cortex. They become “trapped” in the limbic system without explicit memory, or sense of time, so the person is unable to recognize that the danger has passed; the cortex can’t access the limbic system to communicate that the episode is over. So, an emotional reaction becomes frozen in the limbic system, where it’s prone to flashbacks; and, the limbic system actually tends towards haste, paranoia, and jumping to bad conclusions, so the person may develop the type of avoidant and safety-seeking behaviours seen in PTSD. (2)

Trudi Wyatt, MA, RP, CCC is a Registered Psychotherapist and Canadian Certified Counsellor in Private Practice in downtown Toronto. She has been practising for six years and currently works with individual adults on a variety of life challenges such as depression, anger, posttraumatic stress disorder, career choices, anxiety, and relational difficulties.

Sources

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/PTSD%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf), 2013, American Psychiatric Association.

- David Leong, MA, LMFT, Sometimes the Road Home Leads Through Hell: The Power of Telling the Neurological Story of Trauma. In the Therapist: Magazine of the California Association of Marriage and family Therapists. Nov/Dec 2012.

- Packard, P.A. et al, in Tracking explicit and implicit long-lasting traces of fearful memories in humans, in Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, Dec 2014. (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25256154)

- Weiten & McCann, Psychology: Themes and Variations, 2007, p.295-296.

*The views expressed by our authors are personal opinions and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CCPA